“[A]s you know, we’ve inherited quite a budget crunch from President Trump.” – Lisa Simpson

Perhaps I should apologize to the Canadian hardcore band Grade for borrowing, and slightly changing, the title of a song on their 1999 album Under the Radar as the title for this post. (Yes, I realize the Spotify link says 2011. Trust me, the album came out in 1999.)

As I began drafting this post on January 20, President Donald Trump had just left office and his successor, President Joe Biden, had taken office. Most major networks aired tributes to mark the occasion, celebrating the transfer of power with pomp and circumstance in the era of COVID-19. That’s not to say it was a peaceful transition of power.

A look back at the past four years is necessary when it comes to federal spending. Yes, this may get long-winded, but there’s a lot to say about America’s 45th President through this particular lens. Generally, there’s a lot to say about the Trump administration. Some of those things are good. Most of them are bad. I’ll be the first to say that I didn’t particularly care for President Trump. I also didn’t particularly care for his predecessor or his predecessor’s predecessor. Are you sensing a pattern?

I recall writing negatively about Trump long before he actually sought the Republican presidential nomination, with much of that focused on his utter ignorance on trade, hypocrisy, and the fact that he really had no discernable principles. For example, Trump was openly critical of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and other trade deals, but his clothing line was produced in at least a dozen countries not named the United States. One of those countries where Trump-branded products were manufactured, by the way, was China.

Certainly, President Trump had, and still has, a base. Some of his supporters had good reasons for voting for him. Obviously, he pledged to cut taxes, and he followed through on that. (No, it wasn’t the largest tax cut in American history. The tariffs imposed by the Trump administration also undermined the tax cuts in a significant way. Those tariffs, taken together, are the third-largest tax increase in American history.)

President Trump promised to slash regulations and roll back some of the most harmful rules published by the Obama administration. He also followed through on that, although some moves made near the end of his term were bad policy, particularly the Most Favored Nation Rule published by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). This rule essentially imports foreign price controls on prescription drugs.

One of the main problems with the Trump administration was the lack of thought that went into policy priorities. Sure, the administration had an agenda, per se, but it was rarely focused even on its most basic of priorities. When it was focused, a tweet from President Trump would distract the White House or administration in a big way. Unsurprisingly, staffers had their own agendas that were inconsistent with positions publicly taken by either the President or high-ranking White House staff. Administration officials, on occasion, would even lobby against the White House. I experienced some of this, but not as much as others.

Federal spending is an example of one epic failure of the Trump administration. I recall attending a meeting in Eisenhower Executive Office Building in early 2017. The nascent administration was listening to conservative groups’ concerns about the debt ceiling. Congress would soon consider an increase in the debt ceiling, and the administration knew conservative groups were a potential problem. White House staffers wanted to know how to keep us from being a problem.

For the sake of not putting people on the spot, I’ll leave the names of attendees out of this, but the first meeting was small. Virtually everyone in the room told the White House staffers who were there that the best way to address the issue was to get federal spending under control. That meant reforming entitlement programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security.

Now, you’ll be shocked to know that candidate Trump made conflicting statements about the national debt and entitlement programs on the campaign trail in 2016. He told The Washington Post that he would eliminate the national debt in eight years, but he also pledged to “save your Social Security without killing it like so many people want to do. And your Medicare.” Not only that, he wanted big increases in defense spending. There was no chance that the national debt would be reduced.

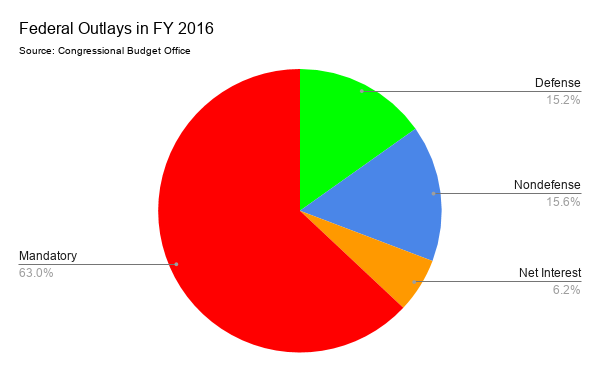

It’s true that most people don’t realize this, but the bulk of federal spending is mandatory. It’s baked in the cake spending tied to either the number of beneficiaries in a program like Medicare or Social Security or net interest on the national debt. The rest is discretionary spending, which is what Congress has debated every year or two since the Budget Control Act of 2011 became law.

According to the Congressional Budget Office’s historical tables, in FY 2016, the last fiscal year before President Trump took office, defense spending represented 15.2 percent of all federal outlays. Nondefense spending was 15.6 percent. The remaining 69.2 percent was mandatory spending. Still, Congress ran a budget deficit of $584.7 billion. In context, that was only 3.2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). That’s not great, but it’s not terrible. (In case you’re wondering why I chose FY 2016 and not FY 2017, the reason is because the appropriations process for FY 2017 wasn’t completed until May 2017, so the Trump administration would’ve had input there. What’s more, the budget agreement under which Congress was operating for FY 2017 was passed before President Trump took office.)

Mandatory spending has long-been recognized as the biggest driver of federal spending and, by extension, the biggest driver of budget deficits. This is because we have an aging population and increasing enrollment in entitlement programs.

So when those of us who met with the White House pointed out that something had to be done about entitlement programs, the response we got back during the meeting was unsurprising but still frustrating. “That’s a fifth-year priority,” the staffer said. There were other ideas floated at that meeting and another one I attended in a large-group setting, including a Swiss-style debt brake to control outlays. As history shows, the White House wasn’t interested. That’s not to say there aren’t staffers who were interested, but the people who mattered weren’t.

Obviously, “a fifth-year priority” was can-kicking. It assumed that there would be a fifth year. There won’t be.

Federal spending continued to rise at an alarming pace even before the pandemic. In February 2018, Congress passed the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, once again busted the spending caps put in place under the bipartisan Budget Control Act of 2011, this time by $296 billion over two fiscal years, FY 2018 and FY 2019. Republicans boasted about defense spending. Of course, President Trump signed it into law.

As an aside, I kept a print out of the “yes” votes for the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 just so I could refer to it when an office reached out to me about a legislative priority. When I put the brakes on a letter of support for one House Republican’s bill because he voted for the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, the member’s chief of staff told me that his boss voted for it because of the defense spending increases and had the audacity to tell me that I “hate the military.” Such a stereotypical response for an office that has clearly taken a sip of the Kool-Aid and can’t own a mistake.

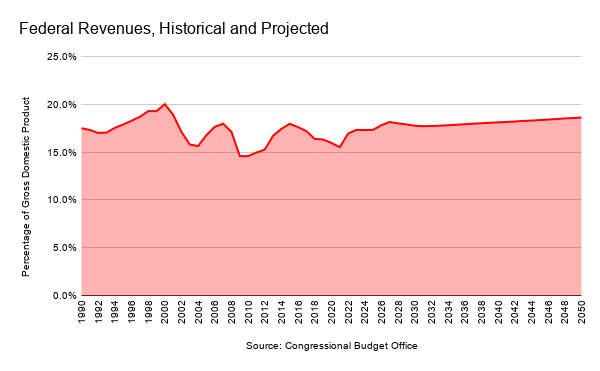

Sure, revenues declined below projections before the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, but the failure to keep spending in check was the larger problem. In July 2019, Congress passed the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019. This time around, Congress busted the spending caps by more than $320 billion over two fiscal years, FY 2020 and FY 2021. Once again, President Trump signed it into law.

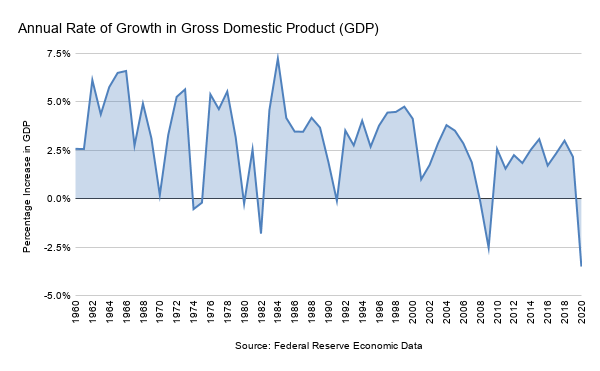

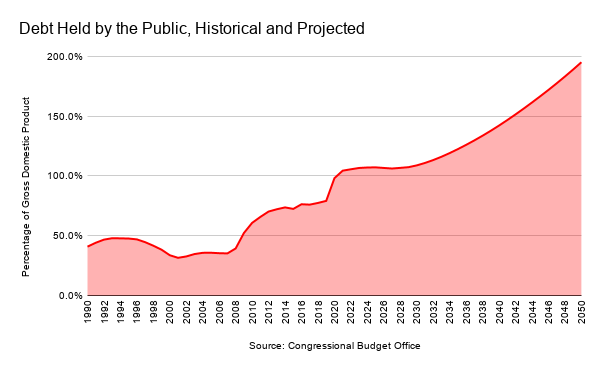

In January 2020, just before COVID-19 hit America, the CBO released its updated ten-year budget projections. (Those projections became largely useless by March 2020 except to serve as a reference point.) In FY 2019, the budget deficit was $984 billion, or 4.6 percent of GDP. Inching up pretty quickly in terms of the size of the deficit relative to the economy. The CBO projected that the budget deficit would exceed $1 trillion in FY 2020 for the first time since FY 2012.

Now, in FY 2012, the budget deficit was exacerbated by an economy that was still recovering from the Great Recession and a neo-Keynesian stimulus bill passed a few years prior. However, prior to the pandemic, the economy was in pretty good shape. (No, it wasn’t the biggest economic boom in American history.)

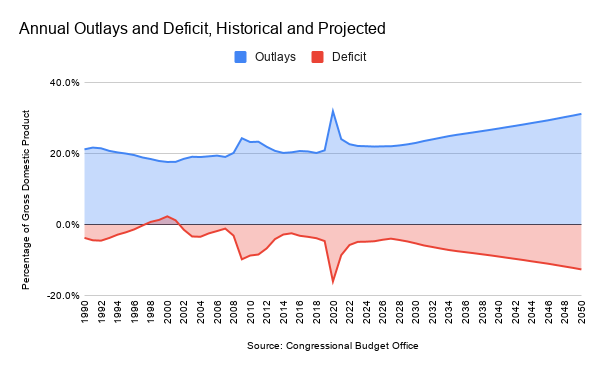

Yet, massive budget deficits were being accumulated in a time of relative peace and good economic times. This was a sign of what was to become the norm. The CBO showed budget deficits exceeding $1 trillion every year for the next ten years. It’s red ink as far as the eye can see. That picture has only gotten worse since March 2020 and the several COVID-19 relief bills Congress passed.

Although the CBO will release updated budget figures in the coming days, the figures released in September 2020 were quite alarming and highlighted the abject failure of the Trump administration to do anything on federal spending. But that’s okay, right, because they released a balanced budgets? Those budgets were never serious, as is usually the case when a president releases a budget.

Of course, spending jumped in FY 2020 because of COVID-19, but it was already on the upswing primarily because the administration’s representatives, primarily Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, were negotiating significant discretionary spending increases behind closed doors and the administration’s unwillingness to do anything about entitlements.

The share of the debt held by the public, which doesn’t include intragovernmental holdings, jumped because of the Trump administration’s pre-COVID-19 spending spree and, then, because of the pandemic and related recession.

It was quite humorous to get an email from a House Republican office asking me to review and lend organizational support to a resolution condemning Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). My response to the request was: “We’re living in [MMT] right now.” There will be those who say that we should take advantage of low interest rates, but those interest rates aren’t going to stay low forever. They will rise as the economy begins to recover from COVID-19, as will the cost of serving the debt.

Now, many will argue that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act caused the increase in the budget deficit. Tax revenues on a purely static basis didn’t decline, although tax revenues as a share of GDP did. I’d agree with the views of some that I’ve read over the years that the tax cuts would’ve been more impactful had they been passed as the economy was trying to recover from the financial crisis.

Even when the individual income tax changes expire at the end of tax year 2025 (assuming President Biden doesn’t repeal them), the CBO projects that tax revenue relative to GDP will remain below the peak of 20 percent in 2000.

There are many failures of the Trump administration, particularly near the end, and too many to list here. But for fiscal conservatives and free marketers among us, the administration’s record on spending is among the worst. Yes, President Biden is going to go on a spending spree, for sure, but President Trump’s four years have left Republicans without any high ground.