Back in August 2011, President Barack Obama signed the Budget Control Act into law. The Budget Control Act came as Republicans, who had the House majority at the time, tangled with President Obama on federal spending and the public debt limit after multiple years of $1+ trillion budget deficits. Those large deficits were caused by the economic contraction that came as a result of the Great Recession and the related legislative responses to the recession.

The Budget Control Act created the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, which was tasked with reducing the deficit by at least $1.5 trillion over ten years, FY 2012 through FY 2021. The Budget Control Act also imposed caps on discretionary spending between FY 2012 through FY 2021.

If the joint select committee couldn’t reach an agreement on a deficit-reduction package of at least $1.2 trillion (yes, that’s $300 billion less than the $1.5 trillion target), automatic caps on discretionary spending would kick in, as well as automatic cuts to nonexempt mandatory programs, to achieve $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction. Because the joint select committee wasn’t able to find an agreement on a package, the autoenforcement caps kicked in beginning in FY 2013.

Discretionary Spending Caps Under the Budget Control Act (Dollars in Billions)

| Fiscal Year | BCA Defense | BCA Nondefense | Autoenforcement Defense | Autoenforcement Nondefense |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | $555 | $507 | $555 | $507 |

| 2013 | $546 | $501 | $492 | $458 |

| 2014 | $556 | $510 | $501 | $472 |

| 2015 | $566 | $520 | $511 | $484 |

| 2016 | $577 | $530 | $522 | $493 |

| 2017 | $590 | $541 | $535 | $506 |

| 2018 | $603 | $553 | $548 | $517 |

| 2019 | $616 | $566 | $564 | $531 |

| 2020 | $630 | $578 | $575 | $545 |

| 2021 | $644 | $590 | $589 | $577 |

Now, President Obama said at the time that he would “veto any effort to get rid of those automatic spending cuts” unless a broader deal on deficit reduction was reached. The Budget Control Act had been in effect for a little more than a year before Congress began worrying about the so-called “fiscal cliff,” an ominous phrase that referred to a mix of spending cuts and tax increases. President Obama signed American Taxpayer Relief Act in January 2013, which delayed some spending reductions and changed tax rates and thresholds.

In March 2013, then-Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) railed about the spending cuts in the Wall Street Journal. He blamed President Obama for automatic spending cuts. The two had tried to reach a so-called “grand bargain” ahead of the Budget Control Act. Boehner claimed that President Obama demanded more revenues than what had been agreed to, leading to the collapse of talks and, ultimately, the passage of the Budget Control Act. Different sides have different stories, but the Washington Post’s recounting of the story largely matches up with Boehner’s side.

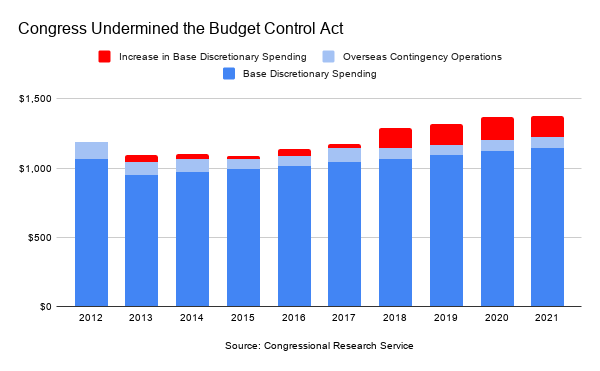

Congress would bust the spending caps four more times through the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 ( busted the caps by $52 billion in FY 2014 and $39 billion in FY 2015), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 ($50 billion in FY 2016 and $29 billion in FY 2017), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 ($142 billion in FY 2018 and $151 billion in 2019), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 ($169 billion in FY 2020 and $153 billion in FY 2021).

Each of these budget agreements, with the exception of one, came when party control of Congress was divided. The one exception was the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, which busted the spending caps by $293 billion over two years. When this budget was passed, Republicans had complete control of Congress, as well as the White House.

Republicans also found a way around the spending caps by funneling money for defense discretionary spending to overseas contingency operations (OCO), which is exempt from the spending caps. Between FY 2012 and FY 2021, Congress busted the spending caps by $803 billion and bypassed the caps for another $872 billion in OCO.

Spending Caps as Amended by Congress (Dollars in Billions)

| Fiscal Year | Base Defense Discretionary | Base Nondefense Discretionary | OCO | Increase Over Caps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | $555 | $507 | $127 | $0 |

| 2013 | $492 | $458 | $93 | +$52 |

| 2014 | $520 | $492 | $92 | +$39 |

| 2015 | $521 | $492 | $73 | +$18 |

| 2016 | $548 | $518 | $74 | +$50 |

| 2017 | $551 | $519 | $104 | +$29 |

| 2018 | $629 | $579 | $77 | +$142 |

| 2019 | $647 | $597 | $77 | +$151 |

| 2020 | $667 | $622 | $80 | +$169 |

| 2021 | $672 | $627 | $77 | +$153 |

Here’s another way of looking at the above.

Of course, the figures for FY 2020 and FY 2021 are different than what the Congressional Budget Office shows in the total amount of discretionary spending. This is because of increases to discretionary spending, totaling $489 billion in FY 2020 and $192 billion in FY 2021 (to this point), passed as part of the legislative response to COVID-19. In a normal year, discretionary spending is roughly one-third of federal spending. None of this includes mandatory spending and net-interest, outlays for which are baked in the cake and not based on congressional appropriation.

Some have pointed out that Republicans lost credibility on federal spending because of the legislative responses to COVID-19. Certainly, the legislative responses to COVID-19 (a great topic for a future post) were significant and dramatically increase federal outlays for both mandatory and discretionary spending, Republicans lost credibility on spending long before the first case of COVID-19 in the United States was ever reported.